PDF For Printing, 3 pages

In Parshat Behar, the Torah severely limits certain types of real estate transactions. A person may only sell his ancestral lands if he really cannot support himself and has no other option. If this does happen, the person who buys the land cannot have too much invested in it; he might be asked to sell it back to the owner or to the family; if that happens, he may not refuse. Even if nobody from the family is able to come up with the money to redeem the land, the seller will anyway have to give it up at the next Yovel, 50th Jubilee, when all lands revert to their original families.

The Torah explains why G-d limits the rights to buy and sell land freely:

וְהָאָרֶץ לֹא תִמָּכֵר לִצְמִתֻת כִּי לִי הָאָרֶץ כִּי גֵרִים וְתוֹשָׁבִים אַתֶּם עִמָּדִי:

The land shall not be sold forever, for the land is Mine, for you are tenants and residents with Me. (VaYikra 35:23)

The land belongs to G-d, and He can legislate and regulate the market however He pleases.

In the Haftarah, Yirmeyahu is asked to redeem land about to be sold by his cousin. Yirmeyahu does so, and makes sure that the sale is performed in accordance with every detail of Torah law, and is fully documented. This would not be in any way remarkable or worth recording in the Tanach, except for the fact that it took place only months before the capture of Yehudah by the Babylonians and the destruction of the Temple, while Yirmeyahu was himself in jail for the treason of prophesying about this destruction. This sale is a prophetic act and comes with an explicit message:

כִּי כֹה אָמַר ה’ צְבָא-וֹת אֱ-לֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל עוֹד יִקָּנוּ בָתִּים וְשָׂדוֹת וּכְרָמִים בָּאָרֶץ הַזֹּאת:

For so said Hashem Tzva-ot the G-d of Israel: “Houses, fields, and vineyards will yet be bought in this land.” (Yirmeyahu 32:15)

This is a beautiful message, full of hope. Yes, the destruction is imminent and in the short term, the deed to this land that Yirmeyahu just purchased is entirely worthless. But one day, there will again be people buying and selling land, and life will go back to normal.

While this is clearly meant to bring comfort and hope, Yirmeyahu gets upset. He turns to G-d and says, roughly, “G-d. You run the world. You took the Jewish People out of Egypt and chose them to be Your people. You gave them this land, and now, because they have been an utter failure at Your mission, You are about to throw them off this land. They are already dying of starvation under siege, more will die in the sacking of the city, and the survivors will be taken into slavery and exile. And you want me to get excited about a real estate deal?!”

It would be as if someone were to go into the Warsaw Ghetto, as people are dying in the streets and the transports to the concentration camps have begun, and tell them, “Don’t worry, I bought land in Tel Aviv, one day it will be worth a lot of money.”

Yirmeyahu does not feel that this is comforting. Yirmeyahu also does not feel that the current situation reflects well on G-d’s influence on history. If He is the owner of the land, and the land is about to be conquered, how will He remain the owner? And of what? A desert? Malaria swamps? So when Yirmeyahu addresses G-d, he says:

הָאֵל הַגָּדוֹל הַגִּבּוֹר G-d who is great, and mighty; (Yirmeyahu 32:18)

He does not say, as Moshe did, “G-d who is great and mighty and awe-inspiring”. The Midrash (Yoma 69b) comments on this omission:

אתא ירמיה ואמר: נכרים מקרקרין בהיכלו, איה נוראותיו? לא אמר נורא.

Yirmeyahu came and said, “Foreigners are about to be prancing about in His palace, where is His awe?” He would not say “awe-inspiring”.

Sitting in jail in Jerusalem under siege, Yirmeyahu could not bring himself to say that G-d is all that awe-inspiring. The Babylonians surely are not showing any awe.

It wasn’t only Yirmeyahu who couldn’t bring himself to say that full sentence. A generation later, Daniel says:

אָנָּא אֲ-דֹנָי הָאֵל הַגָּדוֹל וְהַנּוֹרָא –

Oh, Hashem, G-d who is great and awe-inspiring (Daniel 9:4)

The Midrash explains Daniel’s phrasing:

אתא דניאל, אמר: נכרים משתעבדים בבניו, איה גבורותיו? לא אמר גבור.

Daniel came and said, “Foreigners have enslaved His children, where is His might?” He did not say “mighty”.

The Midrash continues by asking an important question about Yirmeyahu and Daniel:

ורבנן היכי עבדי הכי ועקרי תקנתא דתקין משה!?

But how could they have come and uprooted Moshe’s formulation ?!

If Moshe said, “G-d who is great and mighty and awe-inspiring”, then that must be the way to address G-d. How could Yirmeyahu and Daniel have changed that formula?

אמר רבי אלעזר: מתוך שיודעין בהקדוש ברוך הוא שאמתי הוא, לפיכך לא כיזבו בו.

R’ Elazar said, because they knew about Hashem that He is truthful, and therefore, they did not lie about Him.

Yirmeyahu and Daniel could not use Moshe’s formulation because it contradicted their experience of G-d in this world, and you don’t lie about G-d.

Yirmeyahu did not have personal experience of Geulah, of redemption. He knew, as a prophet, that G-d said that this exile would last only seventy years. He knew, as a prophet, that G-d said that one day life would go back to normal and mundane things such as real estate transactions would take place again. But it is one thing to know it in theory, and a completely other thing to know it from experience. Yirmeyahu’s experience in this Haftarah is of deepening darkness and impending destruction. He could not see the light of redemption, even though he was told that it would come. He did not find it comforting to hear, “Fields will yet be bought in this land”, when he would not live to see the field he just bought.

So how is it that we now say in our prayers, “G-d who is great, and mighty, and awe-inspiring”? Are we lying about G-d?

The Men of the Great Assembly, the rabbis who gathered together during the time of the Second Temple, after prophecy ended, found a way to have this phrase reflect their experience of G-d:

אתו אינהו ואמרו: אדרבה, זו היא גבורת גבורתו שכובש את יצרו, שנותן ארך אפים לרשעים. ואלו הן נוראותיו שאלמלא מוראו של הקדוש ברוך הוא היאך אומה אחת יכולה להתקיים בין האומות?

They came and said, “On the contrary! This is His might, that He overcomes His own wishes, by having patience for the evildoers. This is His awe, for if not for the fear of G-d, how could one nation survive among all the nations?”

The Men of the Great Assembly, having lived through the exile and the redemption, and having been a part of the first Return to Zion, saw things differently than Yirmeyahu and Daniel. They redefined G-d’s power to include situations whose effects are not immediately visible. G-d has power over all the nations, even if you can’t see it just yet. He protects the Jewish People, even if it looks like He has forgotten us completely. He is still the owner of the land, and He will not let it be given over to strangers indefinitely.

The Haftarah of Behar has indeed brought comfort for the Jewish People throughout the centuries.

We have waited for a long time to see these words come to pass, and now that they have, we must not forget how incredible it is that there is a vibrant and flourishing real estate market in the Land of Israel.

הִנֵּה אֲנִי ה’ אֱ-לֹהֵי כָּל בָּשָׂר הֲמִמֶּנִּי יִפָּלֵא כָּל דָּבָר

I am Hashem, the G-d of all mankind.

Is anything too incredible for Me? (Yirmeyahu 32:27)

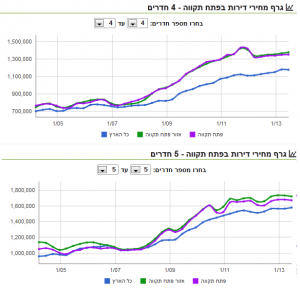

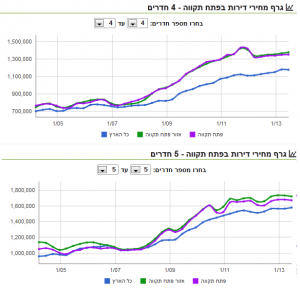

Real Estate prices in Petach Tikvah – a town whose name means: “The beginning of hope”

Copyright © Kira Sirote

In memory of my father, Peter Rozenberg, z”l

לעילוי נשמת אבי מורי פנחס בן נתן נטע ז”ל

Like this:

Like Loading...